The Immigration Divide and its Impact on Latino Opinion

Results from the 2012 Blair Center-Clinton School Poll

Report prepared by Rafael Jimeno, Ph.D.

To gauge the American political landscape in the aftermath of the 2012 presidential election, the Diane D. Blair Center of Southern Politics and Society and the Clinton School of Public Service have conducted a nationally-representative survey of political preferences and behaviors among 3,606 respondents. The Blair Center-Clinton School (BCCS) Poll serves as a follow up and extension of the 2010 Blair-Rockefeller Poll. The BCCS Poll, with its oversample of Latinos, continues to address the dearth of systematic and sustained efforts to compile data that could be used by politicians and scholars who are hoping to understand this dynamic segment of the American populace.

Previous reports have analyzed the differences between foreign-born Latinos and native-born Latinos when it comes to perceptions of Blacks, and also various policy preferences. Such findings add to an increasing body of research that highlights how distinct subsets of the Latino community can be from one another, especially when moving beyond traditional groupings based on country of origin or ancestry.

While building on these findings would be relatively simple (for example, by adding to the list of policies under scrutiny), it would give us little in the way of a comprehensive explanation of these differences. When it comes to a policy position on an issue like immigration, nativity can be expected to exert a great deal of influence over a person’s preferences. What of other policy positions on issues like healthcare or education? What structural factors may account for individual support or opposition on such issues and how do these factors intersect with nativity in the Latino community?

The Proper Role of the Government

The BCCS Poll asked respondents if they believed it was the responsibility of the government to make sure that minorities have equality with whites in several policy areas, even if it meant they would have to pay more in taxes to accomplish that goal. We can begin by looking at healthcare services, which is particularly interesting given the current fight in Washington, D.C., over the Affordable Care Act. Nationally, 55% believe it is the responsibility of the federal government to ensure equality in health services. The figure is much higher when looking at only Latino respondents, a full 73% believe it is the responsibility of the government to ensure equality. This pattern repeats itself in other policy areas (see Table 1).

Table 1. Responses to whether or not the federal government is responsible for ensuring equality between minorities and whites in various policy domains. |

|||||

|

Health Care Services |

Treatment by Courts and Police |

Jobs |

Schools |

Housing |

|

|

Yes |

55% national

73% Latinos |

64% national

75% Latinos |

45% national

64% Latinos |

59% national

72% Latinos |

45% national

61% Latinos |

|

No |

45% national

27% Latinos |

36% national

25% Latinos |

55% national

36% Latinos |

41% national

28% Latinos |

55% national

39% Latinos |

|

Source: 2012 Blair Center-Clinton School Poll |

|||||

The pattern evident in Table 1 is well known, while in general the Latino population is understood to be socially conservative, they tend to be fiscally liberal and favor government intervention to achieve various socially-desirable goals, like equality. However, the gaps are not systematic and for two policy domains, jobs and housing, Latinos actually stand opposite the national trend.

To better understand these discrepancies, this report disaggregates Latino respondents by nativity, given what we know about the impact of this distinction on other policy preferences.

As Table 2 clearly shows, on housing and treatment by the courts and police, there are no differences between native-born and foreign-born Latinos. However, on the other issues there do seem to be gaps, sometimes-large gaps, in the level of support for an activist government. Both subsets of the Latino population are decidedly in the liberal camp, but 5% more of the foreign born stated that it was the responsibility of the government to ensure that minorities had jobs equal in quality to whites than did the native born, for example. Larger gaps are evident for health care services (8%) and schools (9%).

Table 2. Latino responses to whether or not the federal government is responsible for ensuring equality between minorities and whites in various policy domains. |

|||||

|

Health Care Services |

Treatment by Courts and Police |

Jobs |

Schools |

Housing |

|

| Yes | 69% Native

77% Foreign |

74% Native

75% Foreign |

62% Native

67% Foreign |

67% Native

76% Foreign |

61% Native

61% Foreign |

| No | 31% Native

23% Foreign |

26% Native

25% Foreign |

38% Native

33% Foreign |

33% Native

24% Foreign |

39% Native

39% Foreign |

|

Source: 2012 Blair Center-Clinton School Poll |

|||||

A more pronounced concern for socio-economic equality in the foreign-born Latino population only makes sense to the degree that socio-economic differences exist between foreign-born and native-born Latinos and to the degree that these differences are large enough to explain the variation we see here.

Socio-economic Differences

The differences between the native born and the foreign born on almost every socio-economic measure are indeed stark, particularly on education and income.

As evident in Table 3, the foreign-born population of Latinos tends to be much less educated. Almost half (43%) report that their highest level of education is less than high school; compared to 17% of the native born who gave the same response. At the higher end of educational attainment, we also see a large gap. While 19% of native-born Latinos report having a bachelor’s degree or higher, only 8% of the foreign born say the same.

It is perhaps unsurprising then that foreign-born Latinos would be much more likely than native-born Latinos to favor a strong government hand in ensuring equality in schooling.

Table 3. Differences in educational attainment by nativity among Latinos. |

||

| Native-born Latinos | Foreign-born Latinos | |

| Less than high school |

17% |

43 |

| High School |

34 |

30 |

| Some college |

30 |

19 |

| B.A. or higher |

19 |

8 |

|

Source: 2012 Blair Center-Clinton School Poll |

||

For an analysis of income, it was important to collapse the measure into categories for readability. Nevertheless it may be difficult to appreciate the differences between the two populations of interest given that there are six income categories. A good way to think about the information depicted in Table 4 is to note that by the third category (20k to 34,999), we have already described more than half (53%) of the foreign-born Latino population’s income. At that same category, we have only described 34% of the incomes in the native-born Latino population.

The larger degree of support among the foreign born for an active government role in ensuring equality in employment and health care could thus be reasonably argued to stem, at least in part, from a comparatively lower level of income.

Table 4. Differences in income level by nativity among Latinos. |

||

| Native-born Latinos | Foreign-born Latinos | |

| Less than 5k to 9,999 |

10% |

11 |

| 10k to 19,999 |

11 |

19 |

| 20k to 34,999 |

13 |

23 |

| 35k to 59,999 |

25 |

24 |

| 60k to 99,999 |

26 |

16 |

| 100k or more |

15 |

7 |

|

Source: 2012 Blair Center-Clinton School Poll |

||

Structure versus Agency

One final puzzle of importance in this analysis is the degree to which this population of immigrants sees itself as having a role to play alongside that of the government. To investigate this, measures of behaviors and attitudes would be important. It is a large and complex question and, as such, impossible to address entirely in this report. One small bit of evidence comes from responses to questions about the importance of learning to speak English.

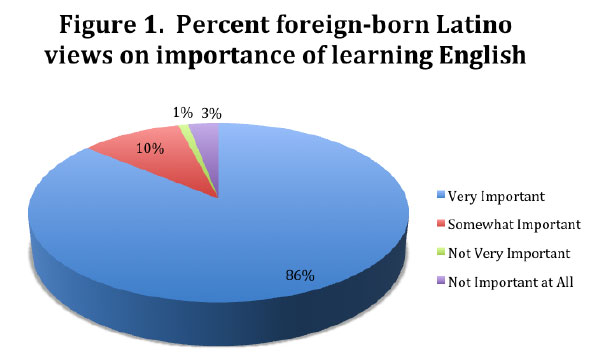

Some proponents of reduced immigration levels, or more punitive enforcement of our immigration laws, assert that immigrants represent a sort of cultural threat to the country. This assertion takes many forms; one variant imagines that immigrants reject American values and culture, as evidenced by their supposed unwillingness to learn the language. The data, however, do not support such assertions.

Not only do Latinos report that retaining the ability to speak Spanish is just as important to them as learning to speak English, but by dividing the Latino population by nativity we see that the foreign born are slightly more likely than the native born to say that learning to speak English is “very important” (86% to 82%). An additional 10% of the foreign born say that learning English is at least “somewhat important” (see Figure 1).

This recognition of the importance of being fluent in English is similar to the level of acceptance that Latinos demonstrate, across numerous other studies, for principles of self-reliance and hard work.

Looking Ahead

There are rational calculations that participants in our political system likely make (even if in cursory fashion) in order to choose a side of a debate. Added to these cost/benefit analyses is the impact that ideological or partisan predispositions may have on one’s preferences. All of these point to a large degree of freedom in deciding what one’s interests are and in pursuing them in the political arena. For many in our polity, however, interests are not a matter of choice, but of need.

Additionally, it is not the case that in requiring the assistance of the government in one realm one fails to recognize one’s own responsibilities.

The Latino immigrant population has socio-economic pressures and needs that cannot be remedied without the support of government. This is quite similar to other ethnic minorities in this country. It is, however, important to have a more nuanced understanding of each community’s particular needs and how those needs impact policy preferences. As should be evident, the impact is not uniform and assuming otherwise distorts the image of the community and makes proper analysis of its members more difficult.

Methodology

Knowledge Networks (www.knowledgenetworks.com), a GfK company, administered the Blair Center-Clinton School (BCCS) Poll immediately following the 2012 presidential election. Its proprietary database contains a representative sample of Americans, covering traditionally hard-to-survey populations such as cell phone-only households and households without Internet access (estimated at 23% and 30% of all households, respectively).

The BCCS Poll has a total sample of 3,606 individuals aged 18 years or older including 1,110 Latino, 843 African American, and 1,653 non-Hispanic white respondents. Across all racial and ethnic categories, 1,792 respondents lived in the South, and 1,814 respondents lived in the non-South. The majority of respondents took approximately 20 minutes to complete the survey. Respondents had the choice to complete the survey in either Spanish or English. The English survey was completed by 3,148 respondents, while 458 completed it in Spanish.

Contact:

D. Xavier Medina Vidal, Ph.D.

Diane D. Blair Professor of Latino Studies,

Assistant Professor of Political Science

University of Arkansas

479-575-7389

dxmedina@uark.edu