Latino Views Diverge Based on Nativity

Findings from the Blair-Rockefeller poll

On the heels of the 2010 midterm elections, the Diane D. Blair Center of Southern Politics and Society, together with Winthrop Rockefeller Institute, conducted a comprehensive online national poll of political attitudes and behaviors. TheBlair-Rockefeller Poll oversampled participants from the Southern region of the United States, as well as oversampling African Americans and Latinos, providing unique perspectives on contemporary politics. With over 3,400 respondents from across the nation, the Blair-Rockefeller Poll provides a comprehensive and uniquely accurate perspective on how the country evaluates public figures and current public policies – and how these evaluations vary across race and geographic region. Following the recent Republican take-over of Congress and the reported GOP gains resulting from voters’ negative reactions to a sluggish economy, the Blair-Rockefeller Poll included several questions asking respondents about their current economic situation as well as their future economic outlook.

Topic Report:

Latino Views Diverge Based on Nativity

By Rafael Jimeno, Ph.D., Assistant Professor, Department of Political Science

While it is widely understood that Latinos are not a monolithic group, it is nonetheless common for the media and politicians to treat them as a single voting bloc. Indeed, much attention is devoted during electoral cycles to the “Latino Community,” in spite of the vast differences that exist between Latinos in terms of race, socio-economic status, and country of origin or ancestry.

A close analysis of the responses given by Latinos reveals that a significant division exists between the native born and the foreign born, especially when it comes to policy preferences and perceptions of other groups in American society.

Policy Preferences

Much of the attention of political elites, both Latino and not, is focused on mobilization, or get-out-the-vote campaigns. While there may be several hot-button topics on which Latino opinions are more or less cohesive, it is also to be expected that many proposed laws will have disparate impacts and thus receive disparate amounts of opposition or support from different Latinos (See Table 1).

While nationally, the majority of Americans tend to favor enacting tougher immigration laws (56%), only 27% of native-born Latinos feel the same way, and an even smaller proportion of the foreign-born (9%) express support. Equally, native-born Latinos express opposition to such a policy at a much lower level than the foreign-born, 49% versus 77% respectively. Community activists were successful in mobilizing Latinos in support of comprehensive immigration reform in 2006 at a series of mass rallies around the nation, but, as noted, the specifics of that reform and how punitive it is toward individuals found to have violated U.S. immigration laws will invariably trigger vastly different responses depending on which segment of the Latino population is asked.

| Table 1. Support and Opposition to Enacting Tougher Immigration Laws Like the One in Arizona | |||

| National | Native-Born Latinos | Foreign-Born Latinos | |

| Favor or Strongly Favor | 56.09% | 26.56% | 9.09% |

| Neither | 20.62% | 24.17% | 13.91% |

| Oppose or Strongly Oppose | 23.29% | 49.18% | 77.00% |

| Source: 2010 Blair-Rockefeller Poll | |||

For example, when asked if they favored or opposed raising taxes to reduce the budget deficit, equal proportions of native-born Latinos and foreign-born Latinos (49%) stated being opposed or strongly opposed to this policy, slightly lower than the national average of 56%.

However, when asked if they favored or opposed allowing same-sex couples to legally adopt children, 31% of the native born opposed or strongly opposed this policy, compared to 41% of the foreign born who felt the same way. The national average was 37%. When asked if they favored or opposed allowing same-sex couples to legally marry, 34% of the native born and 36% of the foreign born said they opposed or strongly opposed this policy, compared to a national average of 42%. These responses also make sense, given that the influence of the Catholic Church should be more pronounced among individuals hailing from Latin American countries. More often than not, foreign-born Latinos will be more socially Conservative than their native-born counterparts.

| Table 2. Latino Responses to Questions about Linked Fate | |||

|

All Latinos |

Native Born |

Foreign Born |

|

|

Commonality with Blacks (job opportunities, education and income)? |

|||

|

None or little |

55.1% |

45.3% |

60.6% |

|

Some or a lot |

44.9% |

54.7% |

39.4% |

|

Commonality with Blacks (political power and representation)? |

|||

|

None or little |

47.1% |

39.5% |

53.0% |

|

Some or a lot |

52.9% |

60.5% |

47.0% |

|

Does what happens to Blacks have something to do with what happens in your life? |

|||

|

None or little |

59.5% |

36.4% |

63.1% |

|

Some or a lot |

40.5% |

63.6% |

36.9% |

|

How much doing well depends on Blacks doing well? |

|||

|

None or little |

53.6% |

47.5% |

60.5% |

|

Some or a lot |

46.4% |

52.9% |

39.5% |

|

Source: 2010 Blair-Rockefeller Poll |

|||

Cooperation with African Americans?

Many scholars assume that due to shared disadvantage in society, Latinos and African Americans are natural political allies. The assumption is that, generally, perceiving that Latinos and African Americans have much in common, or believing that what happens to one group will affect the other is a precursor to political cooperation. In many instances, given the varied backgrounds of Latinos, it is also asserted that before they can see themselves as linked to African Americans, they must see themselves as linked with one another.

Respondents to the Blair-Rockefeller Poll were asked a series of these “linked fate” questions. An analysis of Latino responses to these items, broken down by nativity, reveals how different the native born are from their foreign born counterparts.

As Table 2 demonstrates, Latinos as a whole seem split on most items, though generally leaning toward perceiving themselves as having little in common with African Americans. It is clear, however, that the foreign born feel the least connected to African Americans, and it is they who negatively impact overall Latino responses. Furthermore, contrary to the notion that perceptions of commonality and linked fate among Latinos can extend to African Americans, 65.88% of all Latino respondents said that what happens to other Latinos will have some or a lot to do with their lives, whereas only 34.12% said that it will have little, or nothing, to do. Interestingly, there were no significant differences between the native born and the foreign born on this measure, the gap between the two groups was less than 4%.

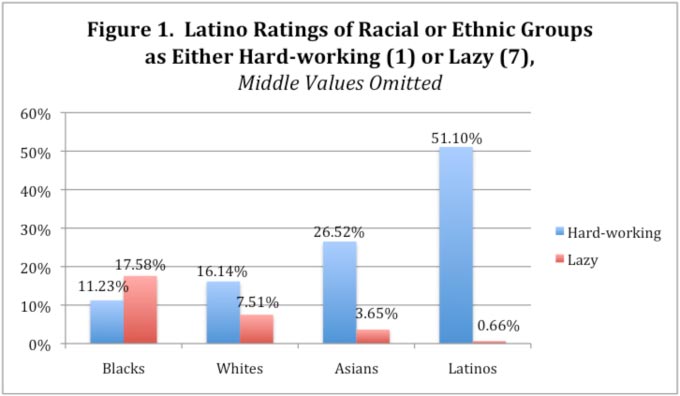

This same negative impact is evident in an analysis of one measure of ethnocentrism (a concept that involves stereotypes about out-groups), in this case, ratings of groups as either hard working or lazy.

It bears highlighting that Figure 1 is a contrast of extreme positions, clearly the bulk of respondents lay somewhere in the middle values that were omitted for legibility. This simple contrast of extreme positions, however, is quite instructive. Latinos rated themselves the most hard-working group by far. As for the various out-groups, it was only African Americans who were seen as being lazier than they are hardworking. Again, however, looking at Latino responses as a whole can be misleading.

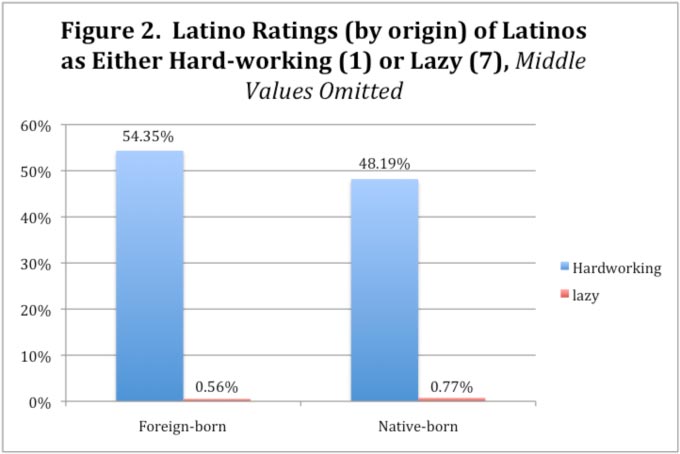

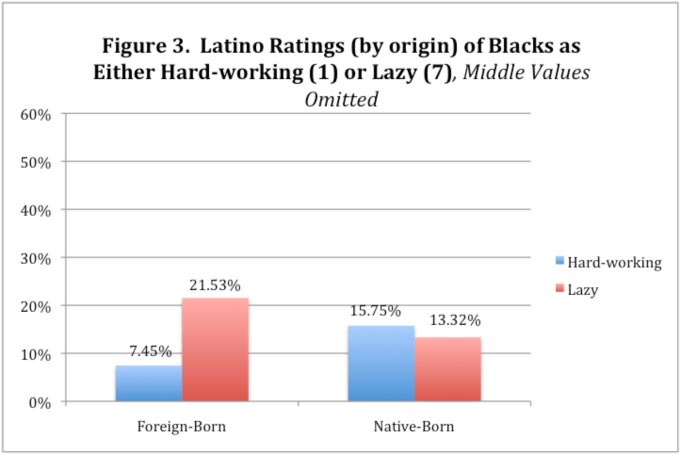

Figures 2 and 3 separate the ratings assigned to Latinos and African Americans by native-born and foreign-born respondents. It is clear, that foreign-born Latinos are more ethnocentric than the native born. In figure 2, over 6% more of the foreign born rated Latinos as hardworking than did the native born…though they both seem equally unlikely to rate Latinos as lazy. In figure 3, whereas as the gap between the two extreme ratings of African Americans by the native born is just a little over 2%, the gap in the case of the foreign born is about 14%.

Looking Toward the Future

Minority community leaders need not despair about these findings. For one, it is entirely possible that Latinos might perceive themselves as dissimilar from, and unconnected to, African Americans and yet still cooperate on key political issues when they emerge.

Further, the fact that this difference between the two Latino subgroups exists points to an origin outside the American context. These negative predispositions of the foreign born likely originate in Latin American countries with pervasive racial hierarchies.

It is encouraging that the native born are much more likely to perceive themselves as linked to African Americans and as sharing things in common with them. It is, after all, these very individuals who will be socializing the foreign born into American society. Over the years, these negative predispositions are likely to recede as the foreign born learn about civil rights struggles, for example, both past and present.

Finally, for various reasons (including an improvement in the quality of life in various Latin American countries over the past decade, as well as declining job opportunities here in the U.S. as a result of the economic downturn) immigration from Latin America seems to have slowed down. The impact of this, if it becomes an enduring trend, cannot be understated, as the very acculturation we know to moderate opinions about intergroup relations will be reinforced in the absence of new cohorts of individuals with markedly divergent views.

Methodology

Knowledge Networks (www.knowledgenetworks.com) administered the Blair-Rockefeller poll immediately following the 2010-midterm elections. Its proprietary database contains a representative sample of Americans; covering traditionally hard-to-survey populations such as cell phone-only households, and households without Internet access (estimated at 23% and 30% of all households, respectively).

The Blair-Rockefeller Poll has a total sample of 3,406 individuals aged 18 years or older including 932 Latinos, 825 African Americans, and 1,649 non-Hispanic white respondents. Across all racial and ethnic categories 1,689 respondents lived in the South, and 1,717 respondents lived in the non-South. The average survey took 21 minutes to complete. Finally, respondents had the choice to complete the survey in either Spanish or English, 2,946 completed it in English, while 460 completed it in Spanish.

Contact:

D. Xavier Medina Vidal, Ph.D.

Diane D. Blair Professor of Latino Studies,

Assistant Professor of Political Science

University of Arkansas

479-575-7389

dxmedina@uark.edu